The Eleventh Sunday after Pentecost, Proper 13, 31 July 2016

Track One:

Hosea 11:1-11

Psalm

107:1-9, 43

Track Two:

Ecclesiastes:

1:2, 12-14; 2:18-23

Psalm 49:1-11

Colossians 3:1-11

Saint Luke 12:13-21

Background: Difficult Prophets

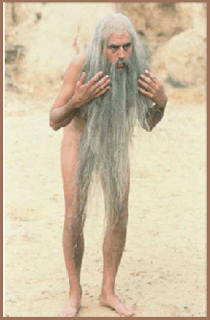

I ran into

an interesting conversation on Facebook this last week concerning Hosea. The

poster wondered if others were abandoning the Track One reading from Hosea in

favor of the Track Two reading because Hosea was just too difficult. One

responder even commented that you couldn’t do just to Hosea in the average

twelve-minute Episcopal sermon. I noted that I am missing the opportunity to

preach on Hosea because he is out of the norm and the main stream. In Monty

Python’s The Life of Brian, we have,

I think, a fairly authentic representation of the ecstatic prophets – crazy

making in their eccentricity. Perhaps that is the difficulty. If we scratch the

surface of religion we find a substratum of the uncomfortable: sexual life,

retribution, xenophobia, and exotic visions among others. That we not delve

into these areas as preachers, or lectors, or just plan students of the Bible

denies us the humanity of the Scriptures, and removes us from similar moments

in our own lives. I find it heartening that Hosea takes the difficulties of his

own life as the context against which he portrays his message. They seem to be

hooks that any person can identify with, and then begin to understand the

prophet’s concern. They dynamics of family life are used to provide examples of

a nation’s relationship with God. It is the prophet’s hope, I think, that the

individual could look at their own life and its quandaries and there begin to

understand God’s message to Israel.

Track One:

First Reading: Hosea 11:1-11

When Israel was a child, I loved him,

and out of Egypt I called my son.

and out of Egypt I called my son.

The more

I called them,

the more they went from me;

the more they went from me;

they kept

sacrificing to the Baals,

and offering incense to idols.

and offering incense to idols.

Yet it

was I who taught Ephraim to walk,

I took them up in my arms;

but they did not know that I healed them.

I took them up in my arms;

but they did not know that I healed them.

I led

them with cords of human kindness,

with bands of love.

with bands of love.

I was to

them like those

who lift infants to their cheeks.

I bent down to them and fed them.

who lift infants to their cheeks.

I bent down to them and fed them.

They shall

return to the land of Egypt,

and Assyria shall be their king,

because they have refused to return to me.

and Assyria shall be their king,

because they have refused to return to me.

The sword

rages in their cities,

it consumes their oracle-priests,

and devours because of their schemes.

it consumes their oracle-priests,

and devours because of their schemes.

My people

are bent on turning away from me.

To the Most High they call,

but he does not raise them up at all.

To the Most High they call,

but he does not raise them up at all.

How can I

give you up, Ephraim?

How can I hand you over, O Israel?

How can I hand you over, O Israel?

How can I

make you like Admah?

How can I treat you like Zeboiim?

How can I treat you like Zeboiim?

My heart

recoils within me;

my compassion grows warm and tender.

my compassion grows warm and tender.

I will

not execute my fierce anger;

I will not again destroy Ephraim;

I will not again destroy Ephraim;

for I am

God and no mortal,

the Holy One in your midst,

and I will not come in wrath.

the Holy One in your midst,

and I will not come in wrath.

They

shall go after the Lord,

who roars like a lion;

who roars like a lion;

when he

roars,

his children shall come trembling from the west.

his children shall come trembling from the west.

They

shall come trembling like birds from Egypt,

and like doves from the land of Assyria;

and I will return them to their homes, says the Lord.

and like doves from the land of Assyria;

and I will return them to their homes, says the Lord.

Between

the parentheses of verses 1 and 11 in which God professes a great love for

Israel, there is a rehearsal of unfaithfulness on Israel’s part and

disappointment on God’s. What is contrasted here is Egypt and Assyria. The

pericope begins with a remembrance of Israel’s deliverance from slavery in

Egypt, but later on there is a substitution for Egypt, “They shall return to the land of Egypt, and Assyria shall be their

king.” The deliverance is incomplete because the people are still in

slavery to the Ba’alim. What God had meant as a return has been realized as a

rejection, and thus the people shall return not to freedom and redemption, but

rather to slavery.

The

last part of the pericope sees some repentance. Not on the part of the people,

but rather on God’s part, “My heart

recoils within me; my compassion grows warm and tender.” What should be

noticed are the images of parent and child, and the behaviors of a loving

family. “I was to them like those who

lift infants to their cheeks.” Many a parent in our midst knows the pain of

having to correct a child, and yet love them. The humanity that Hosea lifts up

here, as he talks about God and God’s people should make for some good

preaching and reading – experiences that remarkably touch our own lives with

understanding.

Breaking open

Hosea:

1. What does

it mean to call God “father” or “mother”?

2. What are

the difficult parts about being a parent?

3. In what

ways does this reading represent a psychological conflict?

Psalm 107:1-9, 43 Confitemini Domino

1 Give thanks to the Lord, for he is good, *

and his mercy endures for ever.

and his mercy endures for ever.

2 Let all those whom the Lord has redeemed proclaim *

that he redeemed them from the hand of the foe.

that he redeemed them from the hand of the foe.

3 He gathered them out of the lands; *

from the east and from the west,

from the north and from the south.

from the east and from the west,

from the north and from the south.

5 They were hungry and thirsty; *

their spirits languished within them.

their spirits languished within them.

6 Then they cried to the Lord in their trouble, *

and he delivered them from their distress.

and he delivered them from their distress.

7 He put their feet on a straight path *

to go to a city where they might dwell.

to go to a city where they might dwell.

8 Let them give thanks to the Lord for his mercy *

and the wonders he does for his children.

and the wonders he does for his children.

9 For he satisfies the thirsty *

and fills the hungry with good things.

and fills the hungry with good things.

43 Whoever is wise will ponder these things, *

and consider well the mercies of the Lord.

and consider well the mercies of the Lord.

The

themes of this psalm resonate with the themes that we have just rehearsed in

the Hosea reading. What might seem to be theological ideas and remembrance is

actually a reading of what was going on politically. The redemption mentioned

in verse two is political redemption, a relief from the oppression of Egypt (or

anticipated in Assyria or Babylon). There are hopeful verses, however, that

speak of return from all the points of the compass, so the psalmist may be

taking the experience of Egypt or of later exiles and making for a generic or

universal understanding of God’s grace. There is also a contrasting of the

people’s cries and their acclaim. One translation of the first verse

underscores the contrast, “Acclaim the

Lord, for He is good.” Later, however, the people are crying in the desert

wastes. The bulk of the psalm, most of which is not used here in the reading

for this Sunday, then rehearses the graciousness of God in answering the cries

of God’s people. Although this is a

psalm of thanksgiving, there is an appeal to the notion of Wisdom in the final

verse, “whoever is wise will ponder these

things.”

Breaking open Psalm 107:

1.

How is the story of

Egypt different that the story of Assyria?

2.

What does

“redemption” mean in this psalm?

3.

What is the wisdom

(common sense) in this psalm?

Or

Track Two:

First Reading: Ecclesiastes 1:2, 12-14; 2:18-23

Vanity of vanities, says the Teacher, vanity of

vanities! All is vanity.

I, the Teacher, when king over

Israel in Jerusalem, applied my mind to seek and to search out by wisdom all

that is done under heaven; it is an unhappy business that God has given to

human beings to be busy with. I saw all the deeds that are done under the sun;

and see, all is vanity and a chasing after wind.

I hated all my toil in which I had

toiled under the sun, seeing that I must leave it to those who come after me --

and who knows whether they will be wise or foolish? Yet they will be master of

all for which I toiled and used my wisdom under the sun. This also is vanity.

So I turned and gave my heart up to despair concerning all the toil of my

labors under the sun, because sometimes one who has toiled with wisdom and

knowledge and skill must leave all to be enjoyed by another who did not toil

for it. This also is vanity and a great evil. What do mortals get from all the

toil and strain with which they toil under the sun? For all their days are full

of pain, and their work is a vexation; even at night their minds do not rest.

This also is vanity.

In

some respects the structure of this selection, chosen by the lectionary

editors, is quite disappointing. It attempts too much, and thus accomplishes

little in allowing us, and the people we are either preaching to or reading to,

to understand Qohelet’s message. So what we are left with are the enigmatic

introduction, which opines that life and all that accompanies it is really

quite ephemeral, a snippet of autobiographical material that repeats the themes

from the first verses, and a longer section from chapter two which represents

Qohelet’s odd perspective of and turn of Wisdom. Readers would be helped

considerably by referring to Robert Alter’s excellent article in his book, The

Wisdom Books: Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes: A Translation with Commentary.[1]

He begins by tackling the concept of vanity, the word that begins the work

proper and that was used by the King James translators. He contrasts the Hebrew

vocable havel (merest breath, or

vapor) which represents “the flimsy vapor that is exhaled in breathing,”[2]

with a much more familiar word, ru’ah (life

breath) that is such an active component in Genesis. In our pericope it appears

only as the wind, “all is vanity and a

chasing after wind”, so complete is his cynicism.

The

closing paragraph of our selection is almost oddly appropriate to our time,

given our current political situation, and the frustration that seems to flow

at every point in our society. Yet, the “cries of the people” (see the Track

One psalm) are not that their efforts are futile, but rather that they have not

resulted in the luxuries and material goods that are supposedly deserved. In

wondering how to preach this text, I would be tempted to challenge the values

that seem to drive us, even in the church. I am reminded of an off-hand comment

by the Bishop of California, Marc Andrus, “Perhaps we need to lose some of the

bling.”

Breaking open Ecclesiastes:

1.

In what ways do you agree with the Teacher?

2.

What do you find disturbing?

3.

What is the “bling” in your life?

Psalm 49:1-11 Audite haec, omnes

1 Hear this, all you peoples;

hearken, all you who dwell in the world, *

you of high degree and low, rich and poor together.

hearken, all you who dwell in the world, *

you of high degree and low, rich and poor together.

2 My mouth shall speak of wisdom, *

and my heart shall meditate on understanding.

and my heart shall meditate on understanding.

3 I will incline my ear to a proverb *

and set forth my riddle upon the harp.

and set forth my riddle upon the harp.

4 Why should I be afraid in evil days, *

when the wickedness of those at my heels surrounds me,

when the wickedness of those at my heels surrounds me,

5 The wickedness of those who put their trust

in their goods, *

and boast of their great riches?

and boast of their great riches?

6 We can never ransom ourselves, *

or deliver to God the price of our life;

or deliver to God the price of our life;

7 For the ransom of our life is so great, *

that we should never have enough to pay it,

that we should never have enough to pay it,

8 In order to live for ever and ever, *

and never see the grave.

and never see the grave.

9 For we see that the wise die also;

like the dull and stupid they perish *

and leave their wealth to those who come after them.

like the dull and stupid they perish *

and leave their wealth to those who come after them.

10 Their graves shall be their homes for ever,

their dwelling places from generation to generation, *

though they call the lands after their own names.

their dwelling places from generation to generation, *

though they call the lands after their own names.

11 Even though honored, they cannot live for

ever; *

they are like the beasts that perish.

they are like the beasts that perish.

The psalmist here does not abandon his worldview to the complete cynicism of the Teacher (see First Reading) but rather gives a harsh assay of what is valuable in the world. That is the wisdom that he wishes to impart – a song sung sweetly upon a lyre, but bitter to hear. The words are not directed exclusively to Israel, but to a more general and universal audience, for this is a wisdom psalm. There is almost a graduated understanding of the vanities of this world, for the poor will dissolve into death before the rich. And yet the fate of the rich is just the same – death and the Pit. The fate of death is the destiny of both the wise and the dull. The phraseology and vocabulary of this psalmist bears an uncanny resemblance to the Teacher.

Breaking

open Psalm 49

1.

How do you think

about death?

2.

Do you talk to your

friends about death?

3.

Are you too young to

talk about death?

The Second Reading: Colossians 3:1-11

If you

have been raised with Christ, seek the things that are above, where Christ is,

seated at the right hand of God. Set your minds on things that are above, not

on things that are on earth, for you have died, and your life is hidden with

Christ in God. When Christ who is your life is revealed, then you also will be

revealed with him in glory.

Put to death, therefore, whatever in

you is earthly: fornication, impurity, passion, evil desire, and greed (which

is idolatry). On account of these the wrath of God is coming on those who are

disobedient. These are the ways you also once followed, when you were living

that life. But now you must get rid of all such things-- anger, wrath, malice,

slander, and abusive language from your mouth. Do not lie to one another,

seeing that you have stripped off the old self with its practices and have

clothed yourselves with the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge

according to the image of its creator. In that renewal there is no longer Greek

and Jew, circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave and free;

but Christ is all and in all!

Paul

continues his teaching to the Colossians about what it means to live in Christ.

Oddly enough, this reading, a part of lectio continua, actually fits in with

the themes of the Gospel and first reading. Paul doesn’t teach us the vanity of

life, but he does insist on the vanity of earthly things when compared to what

Christ offers. His appeal is replete with his usual lists: a list of that which

is earthly (fornication, impurity, etc.), things to get rid of (anger, wrath,

etc.), and a list of human values that are no longer of value (Greek, Jew,

etc.). There is a phrase here that indicates the mystery of this new existence

that Paul calls the Colossians to, “your

life is hidden with Christ in God.” All else must be given up.

Breaking

open Colossians:

- What does it mean to you to be “hidden with Christ in God?”

- What are earthly things that are of no value to you?

- What is your true human status?

The Gospel: Saint Luke 12:13-21

Someone in

the crowd said to Jesus, "Teacher, tell my brother to divide the family

inheritance with me." But he said to him, "Friend, who set me to be a

judge or arbitrator over you?" And he said to them, "Take care! Be on

your guard against all kinds of greed; for one's life does not consist in the

abundance of possessions."

Then he told them a parable:

"The land of a rich man produced abundantly. And he thought to himself,

`What should I do, for I have no place to store my crops?' Then he said, `I

will do this: I will pull down my barns and build larger ones, and there I will

store all my grain and my goods. And I will say to my soul, `Soul, you have

ample goods laid up for many years; relax, eat, drink, be merry.' But God said

to him, `You fool! This very night your life is being demanded of you. And the

things you have prepared, whose will they be?' So it is with those who store up

treasures for themselves but are not rich toward God."

Here we see Jesus as

rabbi, when a man from the crowd asks him a question of casuistry, “Teacher, tell my brother to divide the

family inheritance with me.” Jesus refuses his request by oddly reversing a

situation that involved Moses. Then, the people objected to Moses leadership,

“Who appointed you ruler and judge? (Exodus 2:14)”. Here Jesus

refuses the role, and it is he who turns the question around, “Friend, who set me to be a judge or

arbitrator over you?” Luke doesn’t leave us in suspense, but announces the

meaning of Jesus’ parable in advance of reporting it to us. The themes are

familiar today, “ones life does not

consist in the abundance of possessions.” The parable explores the vapid

(see comments in the First Reading about the translation of the Hebrew vocable havel) nature of what the rich man finds

of value. He is sort of an anti-Job, for God does not allow his wealth to be

taken away, but rather he is given more. Yet, in spite of that, he will still

die, and all that he has achieved will belong to another. We need to think back

to Luke’s version of the Beatitudes, specifically to the woes that follow the

blessings. “But woe to you who are rich, for you have received your

consolation,” (Saint Luke 6:24).

The question must be asked, “What does it mean to be rich toward God?” It is a proposal that is not even considered by

the Teacher of the first reading, nor is it seen as a value. Jesus paints a

different picture. There is something of value and worth, and it is in our

relationship with God.

Breaking

open the Gospel:

1. How is Jesus your Rabbi?

3. What does that mean to you?

After

breaking open the Word, you might want to pray the Collect for Sunday.

Let your continual mercy, O Lord, cleanse and

defend your Church; and, because it cannot continue in safety without your

help, protect and govern it always by your goodness; through Jesus Christ our

Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and

ever. Amen.

Questions and comments copyright © 2016, Michael T. Hiller

Comments

Post a Comment